John Andrews of the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (Instaar) of the University of Colorado reviewed Marjolaine Saint-Pierre’s book Joseph-Elzéar Bernier, Champion of Canadian Arctic Sovereignty in the February 2010 issue of Arctic, Antarctic and Alpine Research.

“The author should be congratulated for her meticulous research on the life of Captain Bernier, and the translator also deserves a round of applause for a translation that reads well and easily.”

Polar Record published Cambridge University Press (2010) also reviewed Marjolaine Saint-Pierre’s book on Bernier: “this handsomely produced book has considerable value as a detailed record of Bernier’s life and times. (…) the numerous and well chosen illustration provide wonderful glimpses of the world in which he grew up and spent his youth, the nineteenth century world of wooden sailing ships and busy North Atlantic trade.” – Janice Cavell

From: Arctic, Antarctic and Alpine Research

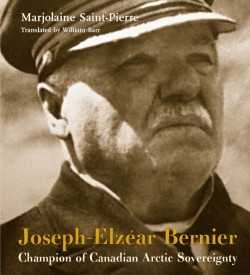

JOSEPH-ELZEAR BERNIER: CHAMPION OF CANADIAN ARCTIC SOVEREIGNTY 1852–1934.

By Marjolaine Saint-Pierre, translated by William Barr. Montreal: Baraka Books, 2009 (originally published in French in 2005). 371 pp. $39.95 Canadian (paperback). ISBN 978-0-9812405-1-0.

Given the political and climatic upheavals of the last few decades, the publication of this biography of Bernier is remarkably pertinent to issues facing Canada and other Arctic nations. Joseph- Elzéar Bernier was a French Canadian who was born in the small hamlet of L’Islet-sur-Mer, on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River in 1852. In this book the author traces the roots of the Bernier family from 1651 when Jacques Bernier landed in Quebec, through the early years of J.-E. Bernier, his subsequent experience as a sailor and captain, and then tracing his passion for Arctic exploration and his importance in ‘‘planting the flag’’ and claiming sovereignty for Canada for what is now its Arctic islands and channels.

Given the political and climatic upheavals of the last few decades, the publication of this biography of Bernier is remarkably pertinent to issues facing Canada and other Arctic nations. Joseph- Elzéar Bernier was a French Canadian who was born in the small hamlet of L’Islet-sur-Mer, on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River in 1852. In this book the author traces the roots of the Bernier family from 1651 when Jacques Bernier landed in Quebec, through the early years of J.-E. Bernier, his subsequent experience as a sailor and captain, and then tracing his passion for Arctic exploration and his importance in ‘‘planting the flag’’ and claiming sovereignty for Canada for what is now its Arctic islands and channels.

This is a meticulously researched book that is richly illustrated by black and white photographs. In addition, it also contains a number of maps that detail the sailing routes and winter harbors that Bernier and the ship Arctic occupied during a number of voyages starting in 1906 and only ending in 1925 when Bernier was 74 years old. It is indeed a remarkable story, and Captain Bernier’s place in Canadian and Arctic exploration should be reaffirmed and reemphasized by this publication.

As a background it should be noted that by an Order of Council in June 1870 Great Britain transferred to the Dominion of Canada all its possessions designated as ‘‘Rupert’s Land and the North-West Territory’’ and a second Order of Council transferred the Arctic islands in 1880 (p. 171). In her discussion of the background to Bernier’s voyages (Chapter 5) Saint-Pierre documents that the object of the Order of Council was to prevent a U.S. claim to these vast, and largely unexplored territories, rather than in a belief that they would have any specific value to Canada. In 1895 the government had divided the Northwest Territories into four districts but this was not immediately followed by any action that would restrict freedom of access to the region by anyone. For example, whalers from the U.S.A. and Britain freely entered the waters with no need for permission of a license.

Captain Bernier’s initial object was to plant the Canadian flag at the North Pole, and he pursued this ambition with great determination starting in 1898. However, the goal of a North Pole expedition was never realized largely because of the vacillations of the Canadian government and the opposition, or reluctance, of Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier.

The name of Captain Bernier is closely associated with his vessel Arctic. This vessel was originally called Gauss, was built in Kiel, Germany, in 1900–1901, and had been used in the Antarctic. Bernier sailed to Germany and took possession of the ship in the spring of 1904. It was 165.5 feet in length with a beam of 37.2 feet; the ship was a three-masted barquentine with an engine that could push her at 7 knots. Given the exploits of this ship it is a tragedy that she was abandoned (see Chapter 23) and was not included in a Canadian Maritime Museum.

For the reader who is interested in the details of the expeditionary cruises, these are documented in Chapters 11 to 16. The chapters are replete with information on the stores that were taken, the track of the ship and ice and weather conditions, the lives of the local Inuit people, including numerous photographs, and how Captain Bernier and the crews coped with the overwintering.

With the steady decrease in ice concentrations in the Arctic Ocean and in the Canadian High Arctic Channels, issues of Arctic sovereignty are now newsworthy and are being discussed at the highest levels of national governments and the United Nations. Whatever the international legal issues that pertain to the conflicting claims of ownership of the various sectors of the Arctic waterways, Canada’s claim to the Arctic islands owes much, if not all, to the vision and persistence of its great French-Canadian polar explorer. Bernier’s position in Canadian Arctic research needs to be elevated; sadly his contribution to exploration is not fully appreciated. The author should be congratulated for her meticulous research on the life of Captain Bernier, and the translator also deserves a round of applause for a translation that reads well and easily.

JOHN ANDREWS

Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR)

University of Colorado, 450 UCB

Boulder, Colorado 80309-0450, U.S.A.

Facebook