AN EMINENT QUEBEC AUTHOR teams up with an anglo sovereignist on a history of French Canada – in English

By Hubert Bauch, The Gazette, July 6, 2009

It doesn’t bother Jacques Lacoursière that he’s commonly called a “vulgarizer.” In fact, the eminent Quebec author and historian revels in what some might take as a slur.

In Lacoursière’s case, it doesn’t mean he’s given to pottymouth. It refers to the further definition of vulgarize, at least according to the Oxford dictionary, which is to “popularize,” and making history popular for the general public and accessible to the average reader has been his lifetime mission.

In his 77 years, Lacoursière has written numerous volumes of Quebec and Canadian history, many of them bestsellers. He says he concentrates on making his historical accounts readable as well as informative, blending great events and personages with revealing tidbits about the daily life of the common folk.

“The important thing for me is that people shouldn’t have to fall back on a dictionary to understand what I write,” he said in an interview. “For me, vulgarization means allowing people, the greatest possible number of people, to understand who they are through their past. Let’s not forget that the most popular edition of the Bible in history has been the Vulgate.”

English readers can appreciate Lacoursière’s approach in A People’s History of Quebec, a new book on which he collaborated with author and publisher Robin Philpot. It is a concise history of Quebec, from the earliest days of colonization to the aftermath of the most recent sovereignty referendum, rendered in an easily read 200 pages. As fascinating as the march of great figures and the mapping of landmark events are the details of how they affected the ordinary life of their times.

For example, the 17th-century debate, during the young colony’s struggling days, over whether the beaver is an animal or a fish. It was highly pertinent at a time when Catholics were enjoined from eating meat during 140 days of the year, though fish was allowed.

Since beaver were in abundance in the struggling colony and if, in fact, they belonged to the fish family, they could be served all year long, and thus the obvious question arose, the book notes. The resident bishop, the towering François de Laval, submitted it to theologians at the Sorbonne and to leading Parisian doctors. “The experts earnestly discussed the issue at length and consulted other illustrious scientists and came down with the conclusion that the beaver was a fish because of its tail. The decision brought joy to the colony.”

It was perhaps not a decisive factor in the English conquest of Quebec, but morale was surely diminished in the French ranks when they were ordered, under threat of hanging, to compensate for a meat shortage while the colony was under siege by eating horses. Their commanders tried to set an example by preparing a meal based entirely on horse meat, including such delights as horse-meat pies à l’espagnole, horse scallops and horse hooves au gratin. “They soon learned that you can put horse meat on the table, but you cannot make the soldiers and the people eat it.”

“There’s a lot of little detail like that about daily life, things that go beyond what I call political and constitutional life,” Lacoursiére said. “It makes the historical account more vivid and more accessible to people who wouldn’t normally read an academic history book.”

This isn’t the first time Lacoursière’s work has been published in English. Back in 1972, a series he wrote on Quebec and Canadian history was issued in 15 slim volumes in collaboration with the Steinberg’s and Loblaws grocery chains and sold in their supermarkets across the country you could check here. Lacoursière says it got him some ribbing from more highbrow historians.

“Some academics asked me if I wasn’t embarrassed to find myself in with a milk carton or a loaf of bread in a grocery bag. I said the important thing for me is that people discover their past, no matter how, no matter where I find myself with that.”

He is not without academic recognition. He has been a visiting professor at Université Laval and been bestowed the Pierre Berton Award by the Canadian National Historical Society and the Académie des lettres du Québec’s medal of achievement. He is a Member of the Order of Canada and a Knight of the Ordre national du Québec. A native of Shawinigan, he is a one-time law school classmate of former prime minister Jean Chrétien.

Noted biographer and journalist Hélène de Billy praises the book as a great read. A People’s History of Quebec is “both an excellent history book to refresh the reader’s memory and a rich introduction to a people who were told (infamously by Lord Durham in 1840) that they had no history.”

Co-author Philpot said the book is intended to fill a current void on bookstore shelves. “For some years now, I’ve heard from booksellers in Quebec City and Montreal that tourists come in and ask them what they have about Quebec in English and there’s really nothing like this. We’re hoping it will serve a purpose in helping people at large better understand where this Quebec identity comes from.”

The book is the first publication issued by Baraka Books, a new publishing house established by Philpot in collaboration with prominent publisher, author and former Quebec cultural affairs minister Denis Vaugeois. Philpot’s contribution to the project included translating Lacoursière’s basic text and adding elements that would appeal to a greater anglophone readership, both Canadian and U.S., pointing out for instance various place names in the United States, such as Detroit, Des Moines and St. Louis, that owe their origin to early explorers from New France, and the fact that O Canada was originally composed as a French-Canadian patriotic alternative to God Save the Queen.

“We hope to make Americans realize that important parts of their history are tied to Quebec,” he said. “In fact, Quebec is at the heart of North American history.”

Philpot, who was born and raised in Thunder Bay, Ont., before settling in Quebec 35 years ago, is best known as a rare anglo sovereignist who ran for the Parti Québécois in the 2007 provincial election. He is a former communications director for the Société St. Jean Baptiste de Montréal and has previously written books highly critical of Canada, including one that alleges the federalist side stole the ’95 Quebec referendum by subterfuge and illegal spending. He sees himself in a line with the likes of E.B. O’Callaghan, Thomas Storrow Brown and the Nelson brothers, who sided with the Patriotes during the 1837 Lower Canada rebellion.

For A People’s History, however, Philpot says he put ideology aside in favour of objectivity. “We took an ecumenical approach in this case,” he said. “Our publishing house isn’t a sovereignist initiative by any means. Maybe some people don’t like to hear that Quebec is an entity with its own history, but it’s an undeniable fact.

Other Baraka books in the works include volumes on early contacts between native and European tribes and on arctic pioneer Joseph-Elzéar Bernier, who staked the Canadian claim to the Arctic Archipelago.

Lacoursière says he would not have it any other way. “If a historian is identified with a political position, then all he writes is judged on that basis. For me, there are no good sides or bad sides – there’s just what happened.”

He does offer the observation that, in the early days of settlement, the French were more venturesome and more accommodating of the continent’s aboriginal peoples than the English. “In the days of the fur trade, the English approach was to build forts and wait for the natives to come to them, while the French traders would go forth to the natives. The contact was altogether different.”

He also suggests that this venturesome “Canadien” tradition has political resonance to this day: “If you psychoanalyze Quebecers as to why they are wary of independence, it is in part because their ancestors crossed North America, two-thirds of which at one point belonged to France. Francophones walked that land.

“Today, if independence were to come, we could think that barriers to the greater continent could arise. One of the features of Quebecers is that they’re at home anywhere.”

If it does come to another referendum, Lacoursière hopes his historical work will help everyone concerned to make an informed decision.

“If one day anglophones and francophones have a decision to make, it shouldn’t be made for sentimental reasons, but rather reflected on in a clear light of understanding.”

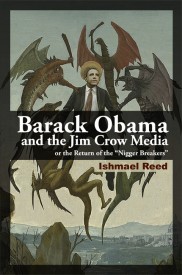

Under slavery, “Nigger breakers” had the job of destroying the spirits of tough black men by whatever means necessary. At age 15 Frederick Douglass was sold to Edward Covey who had the mandate to break him. Ishmael Reed makes the case that President Barack Obama is being assailed by 20th century descendants of Covey. In a series of essays written during the 2008 primaries and after Obama’s election, he shows how both Obama’s opponents and some supposed allies use modern reincarnations of those same ugly demons to break him. What’s more, statements and alliances he made during the campaign and in office have made him easy prey.

Under slavery, “Nigger breakers” had the job of destroying the spirits of tough black men by whatever means necessary. At age 15 Frederick Douglass was sold to Edward Covey who had the mandate to break him. Ishmael Reed makes the case that President Barack Obama is being assailed by 20th century descendants of Covey. In a series of essays written during the 2008 primaries and after Obama’s election, he shows how both Obama’s opponents and some supposed allies use modern reincarnations of those same ugly demons to break him. What’s more, statements and alliances he made during the campaign and in office have made him easy prey. Ishmael Reed’s previous books of essays include Airing Dirty Laundry, Writin’ is Fightin’ and Shrovetide in Old New Orleans.

Ishmael Reed’s previous books of essays include Airing Dirty Laundry, Writin’ is Fightin’ and Shrovetide in Old New Orleans.

Facebook