Two new books in spring 2011.

Break Away, Jessie on my mind; the award-winning young adult novel by

Sylvain Hotte, Translated by Casey Roberts; Illustrated by Pierre Bouchard.

ISBN 978-1-926824-05-5 | $16.95 (April 1 2011; US May 2011)

Alexandre McKenzie lives on North Shore of the St. Lawrence River. In summer he rides the logging trails on his quad. Come winter he isa promising young hockey star who seeks solitude at a bush camp by the frozen lake. But when he plunges into a relationship with a girl plagued by tragedy, things turn ugly. Fighting his own demons Alex fights to hold his head high, like the bull moose that haunts him from the moment he meets Jessie. Break Away tells of friendship, family, pride and love. It’s a story that could happen wherever winter, hockey, and young people come together.

“From the first page it is hard to put down… excellent for teens… characters are lively, likeable and endearing.” Info-culture

“…“ They’re nice, the magic tricks, McKenzie, the fancy plays, the razzle-dazzle…. but I don’t give a damn if we won! That’s not what I’m here to talk about. It’s about you, your game.”

Normally, his lectures made me fidgety and I’d stare at the floor waiting for him to finish. But this time, I held my head up, grinning from ear to ear. My mind was a million light years from Larry’s office. I didn’t care about the game. Didn’t care about his advice or anything else. There was one indelible image planted in my brain: Jessie jumping up and down and cheering her heart out after I scored the winning goal.”….”

Sylvain Hotte is an award-winning writer of fiction for young adults and children. He was born in Montreal to an Innu mother and a Québécois father and now lives in Quebec City. His first series Darhan was astoundingly successful. Break Away, Jessie on my mind is the first book of a trilogy.

Casey Roberts is a translator and editor based in Montreal.

****

THE QUESTION OF SEPARATISM, Quebec and the Struggle over Sovereignty

By Jane Jacobs, with an exclusive unpublished 2005 interview with Jane Jacobs and a new preface by Robin Philpot

ISBN 978-1-926824-06-2 | $19.95 (April 2011)

The incomparable Jane Jacobs passed away five years ago on April 25, 2006. Baraka Books proudly offers readers a new edition of her third, least-known book to mark that anniversary. Undeniably a genius on urban issues, Jane Jacobs also grappled with the question of nations and political sovereignty. Out of print since the mid 80s, The Question of Separatism, Quebec and the struggle over sovereignty now includes a new preface and an exclusive and previously unpublished 2005 interview conducted in Jane Jacobs’ Toronto home just a year before she died. Random House first published the book in 1980.

The incomparable Jane Jacobs passed away five years ago on April 25, 2006. Baraka Books proudly offers readers a new edition of her third, least-known book to mark that anniversary. Undeniably a genius on urban issues, Jane Jacobs also grappled with the question of nations and political sovereignty. Out of print since the mid 80s, The Question of Separatism, Quebec and the struggle over sovereignty now includes a new preface and an exclusive and previously unpublished 2005 interview conducted in Jane Jacobs’ Toronto home just a year before she died. Random House first published the book in 1980.

“There’s no writer more lucid than Jane Jacobs, nobody better at using wide-open eyes and clean courtly prose to decipher the changing world around us.” San Francisco Chronicle.

Jane Jacobs (1916-2006) was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and lived in New York and Toronto. She wrote six other books that have sold in millions, including the groundbreaking The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961).

At the invitation of Gilles Duceppe, Leader of the Bloc Québécois, Guy Bouthillier and Édouard Cloutier presented their new anthology Trudeau’s Darkest Hour, War Measures in Time of Peace October 1970 in the Parliament buildings on Thursday October 21. For Guy Bouthillier, it was an important symbolic gesture forty years after the fact to present this book of texts and speeches by some twenty-five eminent English Canadians about the decision made in the Parliament of Canada on October 16, 1970 to suspend the Constitution and all civil liberties and to send 12,500 troops into Quebec.

At the invitation of Gilles Duceppe, Leader of the Bloc Québécois, Guy Bouthillier and Édouard Cloutier presented their new anthology Trudeau’s Darkest Hour, War Measures in Time of Peace October 1970 in the Parliament buildings on Thursday October 21. For Guy Bouthillier, it was an important symbolic gesture forty years after the fact to present this book of texts and speeches by some twenty-five eminent English Canadians about the decision made in the Parliament of Canada on October 16, 1970 to suspend the Constitution and all civil liberties and to send 12,500 troops into Quebec.

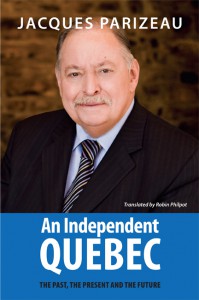

Drawing on his rich experience in public service and teaching, Jacques Parizeau explains how the idea of an independent Quebec took root and evolved, examines Quebec’s current economic, political, social and cultural situation, and reviews options for future development.

Drawing on his rich experience in public service and teaching, Jacques Parizeau explains how the idea of an independent Quebec took root and evolved, examines Quebec’s current economic, political, social and cultural situation, and reviews options for future development.

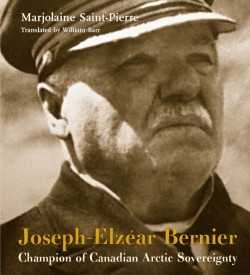

Given the political and climatic upheavals of the last few decades, the publication of this biography of Bernier is remarkably pertinent to issues facing Canada and other Arctic nations. Joseph- Elzéar Bernier was a French Canadian who was born in the small hamlet of L’Islet-sur-Mer, on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River in 1852. In this book the author traces the roots of the Bernier family from 1651 when Jacques Bernier landed in Quebec, through the early years of J.-E. Bernier, his subsequent experience as a sailor and captain, and then tracing his passion for Arctic exploration and his importance in ‘‘planting the flag’’ and claiming sovereignty for Canada for what is now its Arctic islands and channels.

Given the political and climatic upheavals of the last few decades, the publication of this biography of Bernier is remarkably pertinent to issues facing Canada and other Arctic nations. Joseph- Elzéar Bernier was a French Canadian who was born in the small hamlet of L’Islet-sur-Mer, on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River in 1852. In this book the author traces the roots of the Bernier family from 1651 when Jacques Bernier landed in Quebec, through the early years of J.-E. Bernier, his subsequent experience as a sailor and captain, and then tracing his passion for Arctic exploration and his importance in ‘‘planting the flag’’ and claiming sovereignty for Canada for what is now its Arctic islands and channels.

Facebook